Start Strong When Developing or Revising a Large-Scale Assessment Program

Like Any Major Project, Process Matters

One might be tempted to think test development is solely the domain of measurement experts. Not so. When education agencies set out to create a new assessment program or revise an existing one, their efforts are best supported by starting with a thoughtful and wide-ranging development process with a diverse set of contributors at the table.

Launching almost any major project, whether it is building a house, producing a film, or designing a new product, requires a thoughtful, systematic process. Consequential endeavors often involve several phases and should include a range of contributors with diverse skills and expertise. For example, when a software company sets out to develop a new application, the team may need to include coders, network engineers, user experience specialists, artists, marketing professionals, and many others.

Additionally, the process often includes feedback cycles using surveys or focus groups. Ultimately, the strongest development plans are supported by a broad group of contributors with multiple opportunities to gather information and refine their work.

While there certainly isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach, in my experience effective processes share some important features. In this piece, I’ll describe some of those features as they apply to the design and development of an assessment program.

I won’t address the full range of test development activities from start to finish. Rather, my focus is on the first step: developing the initial specifications for the assessment program to promote a strong start, a process which should include at least three phases:

- Discovery: Establish the core purposes, uses, and constraints

- Design: Determine the highest priorities, principles, and corresponding design features

- Dissemination: Broadly share the results and build understanding

Discovery: Establishing the Core Purposes, Uses, and Contraints of the Assessment Program

In the first phase, it is critical to identify the core purposes that the assessment must support. As my colleague Erika Landl describes in a recent post, identifying core purposes means addressing questions such as: Why is the assessment needed? Who is it for? What do you want to do with the results?

It’s important to identify a manageable number of purposes and uses. My colleagues and I at the Center have often quipped, “if you ask an assessment to do everything well, it will probably do nothing very well.” Priorities matter.

In this initial phase, it’s also important to acknowledge any constraints or non-negotiables. For example, if the assessment must meet the federal requirements of the Every Student Success Act (ESSA), those requirements must be established from the start as they may constrain some of the design options and specifications. Other constraints may be related to state laws, state board requirements, or budget limitations. Any aspect of the program that is simply not up for discussion should be clearly named.

Who should be involved in the Discovery phase?

Typically, the discovery phase relies most heavily on senior leaders and policymakers. For example, at a state education agency, the chief state school officer and select deputies or department directors will likely have the most prominent roles in identifying the purposes and constraints. However, it’s not uncommon to cast a broader net at this stage by including board members, legislators, district superintendents, or other influential leaders or experts.

Keep in mind that it’s not particularly helpful to ask these groups to generate a ‘wish list’ for the assessment program at this phase of the project. Rather, it’s important for all stakeholders to understand legal requirements and constraints and then decide on a program scope that supports the core purposes and uses.

Design: Determining the Highest Priorities, Principles, and Corresponding Design Features of the Assessment Program

The design phase centers on further specifying the priorities and principles of the desired assessment system in order to identify the required features and characteristics. Of course, it’s important not to deviate from the core purposes and uses identified in phase one. A well-structured process will help identify promising designs. Instead of randomly ‘shopping’ for an assessment design from a potentially vast range of alternatives, the idea is to develop plausible solutions in a logical and principled manner.

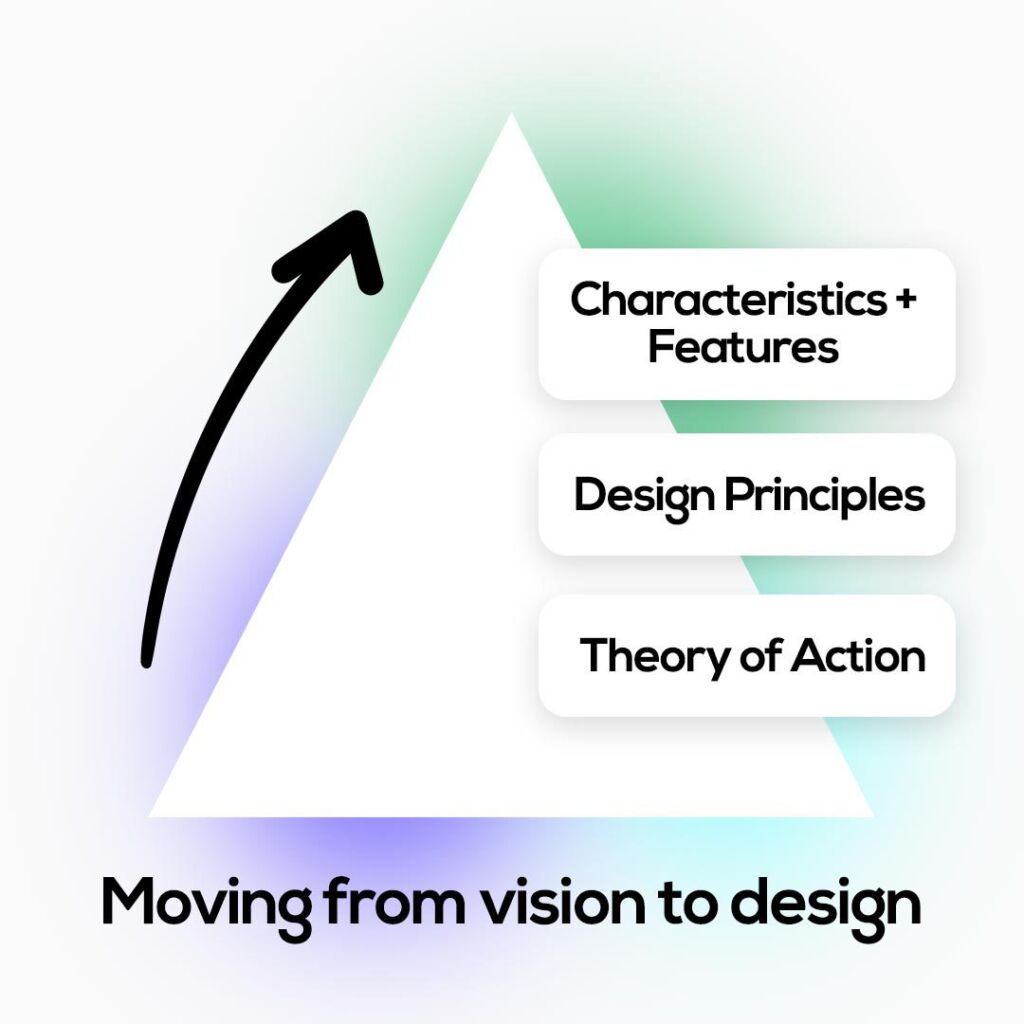

The design process can be thought of as a pyramid, the foundation of which is supplied by the theory of action for how the assessment system is thought to promote the outcomes that are most valued and for how to avoid unintended negative consequences. A complete discussion of theories of action for assessment is beyond the scope of this post, but my colleagues at the Center have written extensively on this topic (see, for example, Dadey and Gong, 2021).

The theory of action describes the main purposes and uses and the core priorities that must be honored. These priorities lead to a set of design principles, which describe the desired general attributes of the system. Finally, decisions about specific characteristics and features of the assessment can be identified.

This process is rarely simple and linear. In my experience, addressing components at each tier of the pyramid allows decision makers to examine and clarify what is important and why.

For example, suppose the priorities for an end-of-year summative assessment include measuring higher-order thinking skills and generating detailed performance profiles to inform instruction. However, a design principle is later proposed that requires the test to be very short and administered quickly. Obviously, these objectives conflict. Resolving that conflict helps clarify priorities and illuminate promising design alternatives. These conversations are essential to developing credible solutions supported by a clear rationale.

Who should be involved in the Design phase?

This design phase presents a great opportunity to hear from a much broader group of experts and stakeholders. Often, it’s desirable to assemble an advisory group comprising a wide range of contributors such as district and school leaders, board members, representatives from community and advocacy groups, parents, and/or students. Depending on the nature of the project and the values of the state (or other sponsoring organization), it may also be desirable to invite business leaders, representatives from institutions of higher education, or other contributors.

Efforts to gain an even broader perspective from stakeholders can be enhanced by conducting surveys or facilitating focus groups.

As with the first phase, it’s best if efforts in the design phase are focused on eliciting priorities among competing interests instead of developing a long list of requests or requirements that are likely too far-reaching to fully implement.

Dissemination: Broadly Sharing the Results and Building Understanding of the Assessment Program

It’s common for the design process to culminate in a capstone report or similar document that describes both the process and outcomes of the previous phases. This document serves to outline the recommendations of the advisory group succinctly but clearly with regard to the assessment program that will be developed and how it should be used. It may also include advice for implementing the recommendations. Ultimately, the capstone report plays a central role in clarifying what is valued, why, and how the assessment program should be designed to promote those values. This clarity is important when it comes time to solicit and evaluate development plans.

Who should be involved in the Dissemination phase?

The person or group who coordinates phases one and two of the process will typically take responsibility for preparing and helping disseminate the final report. While the coordinator may be internal to the agency, often states decide to select an external group for this role. Not only can an external partner contribute expertise to the process, but they may also help the agency maintain a neutral posture when there are competing points of view about the assessment program, as is often the case.

Once the capstone report has been vetted by senior leaders, it’s a good idea to position it as a public document, which can be shared widely with stakeholders to help build understanding and support. It may also be desirable to develop additional communication initiatives such as webinars, videos, or other customized resources for target audiences (e.g., school leaders, and parents). These efforts can promote buy-in, which is essential when it comes time to implement the new assessment.

Moving from Test Design to Development

Once the design recommendations are complete, they must be implemented with fidelity. It’s common for state education agencies to develop a request for proposals (RFP) to elicit plans for test development and administration. When RFPs prominently reference the design recommendations in the capstone report, the proposals developed in response are much more likely to address the priorities of the state. The design recommendations can also provide a means to help evaluate the proposals and guide the work once a partner is selected.

Developing or revising large-scale assessment programs are always consequential endeavors. It’s important to launch the project with a well-structured process informed by a broad group of experts and stakeholders. Ultimately, a strong start helps the agency make steady progress and build sustainability.