You Can Get the Accountability System You Want (Part 2)

Beyond ESSA: Three State and District Examples

Many states complain that the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2015) makes it impossible for them to have the accountability systems they really want. In my previous post, I showed that by minimizing ESSA’s impact on their school identifications, states can create the space to build and operate accountability systems that reflect their goals and values. In this post, I’ll share some examples of states’ and districts’ non-ESSA accountability systems.

These accountability approaches may be distinguished by differences in their who, what, when, how, and why. I’ll highlight just three approaches in this blog.

One is an approach that keeps ESSA’s same basic school accountability architecture, but adds considerable flexibility for additional indicators. Another draws on the school accreditation process to offer a very different approach to how a state might hold schools accountable. Accreditation, in contrast to traditional outcomes-based accountability, shifts the focus to place greater emphasis on the quality of learning opportunities. The third approach illustrates a very different locus of governance, with a shift from the state to the district. (See Table 1.)

| Accountability Approach | |||

| Features | Expanded ESSA | Accreditation | Local/District) System |

| Who/ governance | State governs what, when, how, and why; state may cede some control to districts for what and why (localized indicators) | State governs what (usually); district/school in charge of gathering evidence (usually). Often evidence evaluated by an accreditation agency, not the state | State supports district creation of local accountability system, often aligned to purposes established or endorsed by state |

| What/measures | Expanded set of outcomes (local choice approved by state) | Wide range, including outcomes and inputs (instruction, leadership, etc.) | Wide range, including individualized outcomes and inputs (instruction, leadership, etc.) |

| When | Same as ESSA: annually at or after end of year | Varies (many elements longer-term than ESSA) | Varies (many elements within the school year |

| How evaluated | Similar to ESSA: summative, outcomes-based | Summative, inputs-based | May be summative but often more formative |

| Why | Provide fair, objective, state-approved evaluation for public reporting to support monitoring and evaluation | Provide fair, objective, state-approved evaluation for public reporting and district improvement | Focused on district and school improvement and local accountability |

The “Expanded ESSA” Model: Different Measures Chosen by “Good Schools”

One common complaint is that ESSA does not permit a state or schools to measure what they really value because the ESSA indicators must carry so much weight that any additional indicators deliver little impact.

One solution to this problem is to have the ESSA system include only ESSA-required measures and use them to fuel—but minimize—ESSA-required school identifications. This leaves the large majority of schools identified as “other.” The state then applies its desired non-ESSA accountability system to these schools.

As I’ve written previously, states vary widely in the percentage of schools they identify for support under ESSA. This creates an opportunity: Most of a state’s schools can be monitored and supported by its own accountability system.

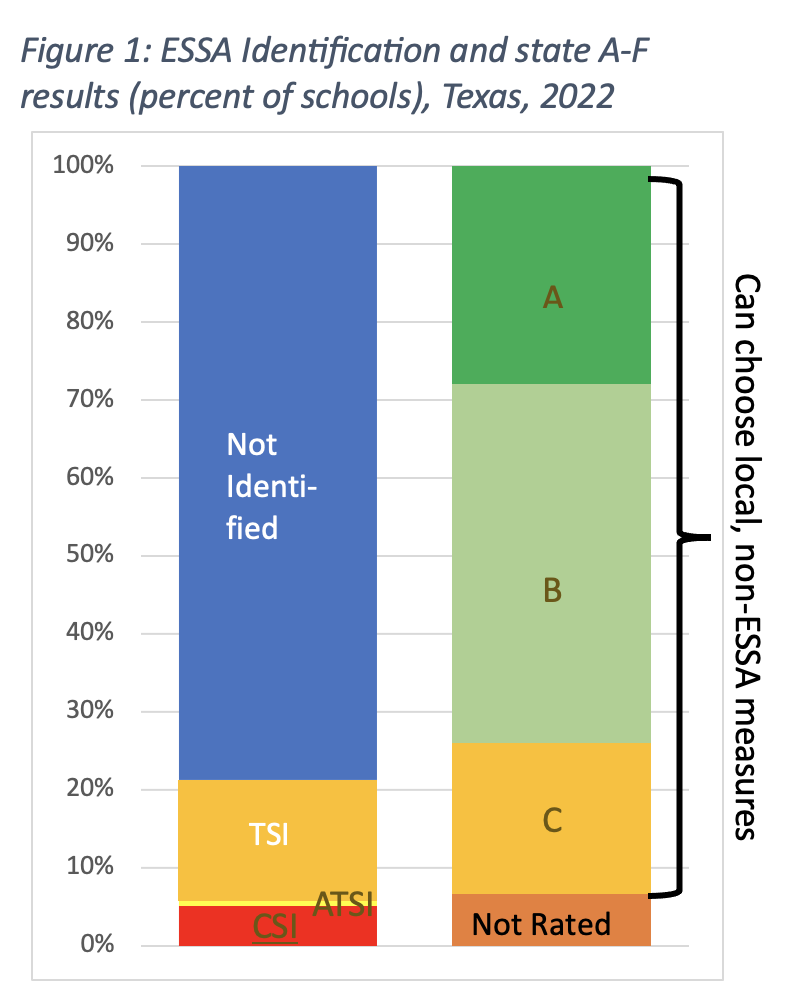

Texas uses the ESSA-required measures as the basis for ESSA-required school identifications, in parallel with a state A-F rating. Figure 1 shows that in 2022, Texas identified a very small number of schools for CSI (5%) or ATSI (<1%), and about 16% for TSI. About 79% were “Not Identified.” Schools that are rated at least a “C” in Texas’ state grading system may opt to use district-and-state-approved local measures to generate an alternative accountability score. The school receives the higher of the two ratings: the rating based on the ESSA indicators, or the rating reflecting the local indicators. In 2022, about 7% of Texas schools were “Not Rated” (the state legislature suspended D and F grades for 2022 due to the pandemic); the remaining 93% of schools were eligible for the state’s local accountability program.

This approach has several features worth noting. It allows the state to keep the basic structure of its outcomes-based accountability program, including its A-F rating system, and the general structure of measuring school performance by indicators and weighting them to create an overall score. Notably, having a parallel system allows the state to incorporate measures that do not have to go through federal approval and that count at different weights than would be possible with an ESSA-only system.

Texas has chosen to allow some degree of localization of measures, responding to calls to recognize that schools may emphasize different things to make their educational offerings reflect community priorities. At its core, this localization recognizes that there should be many ways for schools to be rated highly, while maintaining a common minimum definition for “unacceptably performing” schools (the state definition for D- and F- rated schools, federal definition for CSI, etc. schools).

The Accreditation Model: Quality of Learning Opportunities

Many states require districts and/or schools to be accredited, either by the state’s own panel or a recognized accreditation agency. Accreditation may be viewed as another part of the state’s accountability system. While federal accountability measures are almost all outcomes—particularly student test-based performances—accreditation systems typically focus on supports for learning as well as outcomes. Accreditation requirements depend on the state.

Virginia’s accreditation system, for example, uses elements that are very closely related to the outcome measures in the state’s ESSA accountability system. In contrast, South Carolina’s accreditation focuses on more traditional “inputs,” such as personnel credentialing, mandated curricular areas, maximum student/teacher ratios, and so on.

Kansas has a hybrid approach: its accreditation focuses on the processes districts use to improve performance on state accountability. Virginia and Kansas identify a very low percentage of schools through their ESSA-compliant accountability systems (in 2023, 6% and 11%, respectively, for CSI, ATSI, and TSI, combined), while South Carolina identified a moderate percentage of schools (in 2022, 5% CSI, 2% TSI, and 28% ATSI).

| Accreditation and Accountability | |||

| State | Accreditation Elements | ESSA accountability decision informed by accreditation? | Governance |

| Virginia | Similar to state’s ESSA accountability: grad rate and test-based attainment and gaps; chronic absenteeism | Yes – school accreditation is a factor in whether a low performing school is identified for ESSA school improvement; accreditation alsomonitored and enforced on its own | State controls definition of elements, process for implementation, and use of outcomes in accountability |

| South Carolina | Personnel, curriculum and instruction, operations, and procedures | No – state conducts a separate accreditation evaluation; Consequences for not being accredited are separate from ESSA accountability | State controls definition of elements and process for implementation for state-option; districts have option to use regional accreditation agency, which gives districts more choice over certain aspects |

| Kansas | Evidence of improvement in student performance, and evidence of continuous improvement process (process, fundamentals, outcomes) | No – accreditation is framed as a continuous improvement process, but outcome goals and evidence linked to same indicators as accountability | State controls definition of general elements but districts have extensive discretion on defining how they will generate evidence. State provides extensive supporting materials, coaches, and other resources. |

Accreditation systems’ indicators may go well beyond states’ ESSA indicators to include important supports for learning at the individual, class, school, and district levels. Evidence may draw on qualitative as well as quantitative factors.

The Local District/Accountability Model: Accountability To Deliver

A third approach explores centering accountability in the district communities more heavily than in the state. One example can be found in the way high school graduation requirements are set. States typically establish very general guidelines (e.g., minimum number of credit hours for certain courses), and districts are free to add and fill in. This has led to graduation requirements that differ across districts.

Another example is found in districts that develop competency-based systems. Such districts set their own requirements for—and assessments of—academic and 21st century skills, often involving extended performance assessments.

Even if the state establishes a general framework such as a “portrait of a learner,” the district has considerable authority over the specific requirements, control over gathering the evidence, and responsibility for evaluating the quality of the evidence. The state yields control to the district; district assessments of graduation qualifications are outside the purview of federal peer review, and the state implicitly acknowledges that it does not need strict comparability of graduation rates across districts.

Kentucky is experimenting with a more radical version of the state sharing control over assessment and accountability with districts. Districts involve community partners in deciding what will be instructed and assessed, and how. Districts use the information to evaluate student performance but also to hold themselves accountable to their communities.

By strengthening local accountability, the state hopes that the state’s role can be reduced. The intent is that eventually the district assessments will replace the state assessments, and the state’s federal accountability system will consist of a “system of local systems.” Kentucky is investigating roles for the state, including setting minimum criteria (similar to graduation requirements), and establishing an accreditation-like process.

Minimizing ESSA To Create The Accountability System You Want

States and their partners can operate two accountability systems in parallel: The one required by the federal ESSA law, and another one they design to more fully reflect their goals and values. They can get the bandwidth to operate the latter by minimizing the impact of the former.

Their chosen accountability systems offer a wide range of possibilities, in the way they’re structured, their purpose, and their choice of indicators. However a state envisions its ideal accountability system, it cannot claim with accuracy that its hands are tied by federal requirements. I encourage every state to design and implement the more balanced accountability systems it values.