You Can Get the Accountability System You Want (Part 1)

Without Waiting for ESSA Reauthorization

Since 1994, federal law has required states to have school accountability systems as a condition for receiving Title 1 funds. States often claim that federal requirements make it impossible for them to have the kinds of accountability systems that reflect their values and goals. But under ESSA—the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015)—states have far more freedom than they might realize to pursue the goals and accountability systems they desire and still comply with federal requirements. The rub is that they must know what kind of accountability they really want; they can’t claim with accuracy that federal law binds their hands on all aspects of accountability.

In this blog, I’ll first show how ESSA’s specificity on accountability binds states but also frees them. I’ll briefly show how some states have used this flexibility to reduce the practical impact of ESSA’s restrictions so much that they can focus on their desired accountability systems. In my next post, I’ll share some examples of states’ and districts’ non-ESSA accountability systems.

States can minimize ESSA’s impact so they can focus on the kinds of accountability they value most. But they need to envision the systems that will produce the results they want.

What Kind of Accountability?

Federal accountability is built on a goal of reducing achievement gaps. The underlying theory of action is that identifying low-performing schools—and student groups within schools—and providing supports will lead to improvements in performance. Performance is measured by required assessments and other approved indicators. Supports include financial and other resources, such as guided improvement planning. But many have questioned that theory of action and called for better approaches to accountability.

My intention in this blog post is not to help states avoid having any accountability system. I am a strong advocate for accountability. But I think it would be helpful if states unleashed their creativity and developed accountability systems they and their constituencies believe in and will support enthusiastically. My challenge to states and their partners is to develop accountability systems that reflect their goals and values. And they don’t need to wait for ESSA reauthorization to do so.

ESSA Accountability Requirements

There are six main ESSA accountability requirements. Five are about identifying lower-performing schools:

- States must identify annually schools that have at least one “underperforming” student group, as defined by the state. These schools are designated as in need of “targeted support and intervention” (TSI).

- States must identify schools that have at least one “consistently underperforming” student group, defined as performing at or below the level of all students in the “bottom 5th percentile” of its schools; the state may add additional requirements. These schools are designated as in need of “additional targeted support and intervention” (ATSI).

- States must identify public schools performing in the “bottom 5 percent” on the state’s accountability scoring system, as well as any high schools with a four-year graduation rate less than 67 percent. These schools are designated as in need of “comprehensive support and intervention” (CSI). States must make CSI identifications at least every three years.

- The state establishes “exit criteria” for schools identified for CSI, ATSI, or TSI.

- Any CSI, ATSI, or TSI school that does not exit within the time period established by the state is subject to being reclassified for support at a more serious level: TSI becomes ATSI, ATSI becomes CSI, and CSI schools face additional consequences.

ESSA’s sixth requirement applies to all public schools.

- States must report the accountability results of each public school annually. At a minimum, they must report accountability scores and whether schools were identified for TSI or were previously identified for CSI or ATSI and have not exited, or Other (none of the former). CSI or ATSI identification does not have to take place annually, unless the state decides to do so.

In this blog post, we focus only on ways to minimize the school-identification footprint of ESSA. But the law rests heavily on annual testing, and there are ways to minimize that aspect of the law’s impact as well. We’ve just completed a study on this and will release results soon. In the meantime, read a preview of our findings on how to reduce federally mandated K-12 testing.

Minimizing ESSA School Identifications

There are two ways states can minimize the impact of ESSA’s school-identification requirements, clearing the way for them to implement their own preferred accountability system. States can:

- Minimize the number of schools identified as CSI, ATSI, or TSI

- Refrain from using A-F, 5-star or other designations. States would identify schools only as CSI, ATSI, TSI, or Other.

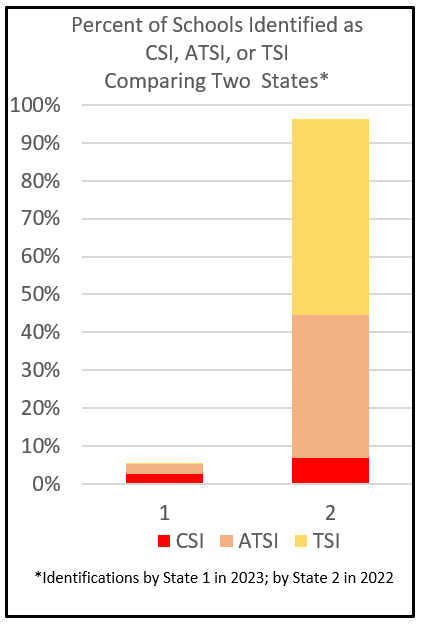

It is clear that states already have—and are using—the considerable latitude ESSA provides in the percentage of schools they identify for support in their federally approved accountability systems. By checking states’ websites, I found that the percentage of schools identified for CSI across the states ranges from about 3 percent to more than 5 percent. Similarly, the percentages of schools identified for ATSI range from less than 5 percent to over 40 percent; for TSI the range is about 1 percent to about 50 percent.

It is not my intent to provide a “how to” manual outlining all the ways states can minimize school identifications with the approval of the U.S. Department of Education. But reviewing states’ ESSA accountability workbooks, all available online, yields many approved ways. Here are just two possibilities:

- How can a state identify only a very small percentage of schools for CSI when ESSA requires “the bottom 5 percent”? One way is by taking advantage of ESSA’s permission to identify CSI schools only every 3 years, rather than annually. Another is to identify only Title 1 schools, as permitted by federal law. (Nationwide, only 66 percent of public schools are Title 1.) A state may also set exit criteria that are easier to meet.

- How can a state identify a very small percentage of schools for ATSI when ESSA requires “the bottom 5 percent performance” criterion for all students to be applied to student groups, many of which are typically lower performing? A state may decide that to be identified for ATSI, a school has to meet the bottom 5 percent performance rule, but must also meet additional requirements, such as having to be identified for TSI first, and/or having to be identified for the same student group multiple years in a row.

Minimizing ESSA’s impact does not mean sidestepping it altogether. Some schools will be identified for CSI, ATSI, and TSI, and states must report their accountability scores and ratings. But some states have figured out how to create and communicate about separate state and federal accountability results, emphasizing the results from the accountability system they feel merits the most attention.

What Next?

If a state chooses to construct its ESSA accountability system to minimize its impact on schools, what will it choose for its own system: nothing? Or something that better matches its vision of productive accountability? How will the state know that this system is better? Those are some of the challenges facing states and those who advocate freedom from federal constraints. Perhaps the central question is this: Now that you know you have freedom to minimize ESSA’s footprint, what will you do with that opportunity?