Does School Accountability Have to Be So Complicated?

Three Keys to Building Less-Complex—but High-Quality—Accountability Systems

“Keep it Simple.” That’s one of the most common requests I hear when I work with education leaders on the design of school accountability systems. To be fair, I’ve seen some accountability systems that appear to be little more than Rube Goldberg machines. Overly complex systems aren’t just difficult to understand and implement; they can erode public confidence. Users don’t intuitively trust things that defy clear explanations.

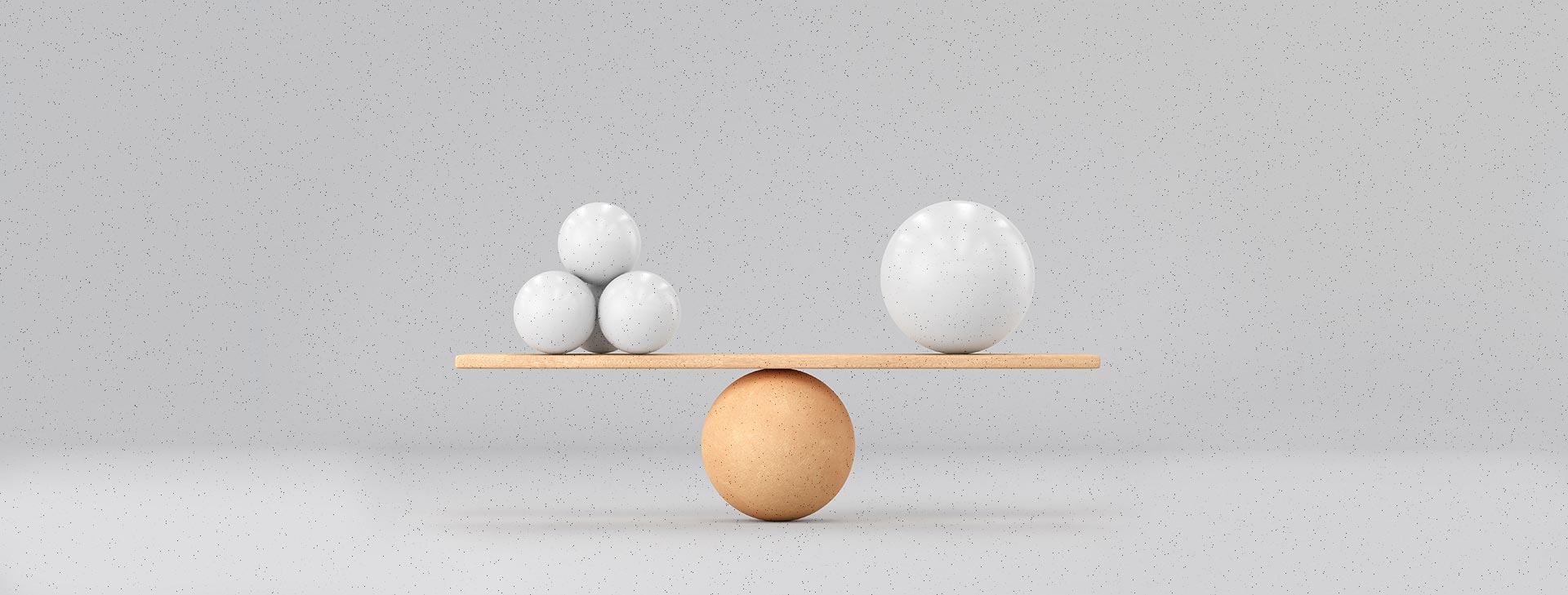

On the other hand, there’s a risk of oversimplifying systems. I’m reminded of H.L. Mencken’s quip, “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” Sometimes very simple approaches fail to address important conditions or nuances. For example, current accountability systems often include detailed formulas that are necessary to produce comparable results for schools with small n-sizes or less-common grade configurations.

Ultimately, balancing simplicity and complexity requires a trade-off. Think of designing school accountability systems like packing for a trip. You can pack light and move more quickly and efficiently through the airport, but you might have to do without bulky, less-necessary items. Or you can choose to juggle more bags, comforted by knowing you’re well-equipped to handle most situations. Most travelers seek a balance.

Similarly, accountability designers should seek solutions that are only as complex as necessary. Here are three principles that I believe can help education leaders create school accountability systems that are simpler without compromising quality.

Clarify Priorities

First and foremost, it’s important to be clear about your priorities. My colleagues at the Center have written extensively about the importance of a theory of action to guide accountability design, which starts with identifying the central goals of the system and the conditions required to achieve those goals. If the pursuit of simplicity undermines your guiding theory of action, it’s not a virtue.

Being clear about priorities can also help designers focus their efforts. For example, policymakers may have placed a higher priority on creating a system that encourages progress for students scoring below the proficient mark than on one that rewards continued progress for students who are at or above proficient. Clarifying this priority helps designers pinpoint which areas of the model they should build out and which ones they can streamline without compromising the central goals of the system.

In sum, if we clarify and streamline priorities, we can pursue less-complex systems that do fewer things well.

Avoid Superfluous Improvements

The principle of parsimony is a useful guide for many things in life, including accountability design. This means that state leaders should consider a solution with fewer parameters, even if one with more is slightly better. Here’s an example. Most people would prefer a test with 40 items and a reliability of .95 (which is quite good) to a test with 50 items and a reliability of .96. The tiny gain in reliability doesn’t justify the added burdens of a longer test.

Accordingly, we should avoid adding measures that bring little value to accountability systems. I’ve seen things added to systems, such as additional tests, or more complex scoring models, to pursue very slight improvements, to address rare ‘what ifs,’ or in a well-intentioned attempt to satisfy every stakeholder request. It may seem harmless to add any one of these measures or features, but the cumulative impact can produce an unnecessarily complex, burdensome system.

Focus on Reporting and Use

Many tools in our daily lives are highly complex, but they’re widely accepted because we can interact with them easily and they add genuine value to our lives. Consider the smartphone, which is a marvel of complex engineering, but that complexity lies under the surface. As users, we get the pleasure of a very easy and intuitive interface that lets us read a text, check the weather, or listen to music with just a few taps.

This idea also applies closer to home, in assessment. Most people recognize that large-scale tests are built on relatively complex item response theory (IRT) models. But people generally accept that complexity when they understand what the results mean and how they can be used.

My point is this: We must reduce the complexity and improve the utility of accountability reporting systems if we are to reach another crucial goal: helping stakeholders understand and leverage results to improve outcomes for students.

What does this look like? Here are some promising practices:

- Create very clear, attractive reporting systems that make the most of graphic features—and minimize text and dense tables—to communicate the key messages.

- Produce resources that invite intuitive and dynamic interaction for a broad range of stakeholders. For example, is it easy to see results by student group or compare results across years?

- Curate resources, such as user guides or videos to support understanding, and demonstrate different ways the results can be used.

- Conduct webinars or workshops tailored to the needs of different user groups.

A Final Thought: Stability Matters

Simplicity is important for all the reasons I’ve outlined. But it also goes hand-in-hand with another crucial goal: stability. Once an accountability system is designed, education leaders should carefully consider the costs of making repeated changes; they generally create more complexity.

Each system change requires new efforts to meaningfully interpret and use results and adds to the perception that the model is dense and inscrutable. When accountability models are more stable, the state’s work to support the public’s understanding and use will yield rewards, and local initiatives will also have time to develop and flourish.