Advancing Contemporary Validity Theory and Practice

Based on Remarks Given During a Town Hall Session at the 2022 NCME Conference

I was honored to participate in a validity “town hall” at last week’s NCME conference with Suzanne Lane, my co-author of the validity chapter in the upcoming 5th edition of Educational Measurement, and Greg Cizek, Professor of Education at the University of North Carolina. It’s no secret that Greg and I have had some disagreements about validity theory and validation over the years, particularly about the role of consequences. It was a lively session, but Jon Twing, Senior VP at Pearson, kept control of things as the moderator.

The Town Hall was well-organized by Greg, included short prepared remarks, questions from the moderator, free-flowing discussion among the participants, and plenty of time for audience interaction. Validity theory can get esoteric in a hurry, so, at least for the prepared remarks, we tried to be practical. Each of the panelists had three minutes to respond to the following two questions:

- What aspect of modern validity theory do you think most supports the practice of validation?

- What aspect of modern validity theory do you think most hinders the practice of validation?

Since I prepared my responses in advance (some might be surprised by this), I decided to share them in this post.

Arguments and Validation: The Aspect of Modern Validity Theory That Most Supports the Practice of Validation

I think the shift to an argument-based approach has been and can be very helpful in conducting validity evaluations. Michael Kane is credited with this framework, which is spelled out in his 2006 chapter in the 4th edition of Educational Measurement. However, the ideas certainly trace back to Cronbach’s work in the 1970s and even earlier. There’s also no question that Messick’s theoretical contributions were seminal, although we still spend as much time trying to parse Messick’s words as so-called originalists work to decipher the intent of a bunch of guys in a hot Philadelphia convention.

Kane’s argument-based approach provides a practical framework for outlining potential claims for which the test user/developer would want to collect evidence. These claims, organized within broad categories of inferences (e.g., generalization) provide a way for evaluators to design and carry out studies in a systematic way.

However, Kane’s approach can get complex if one creates a network of claims, warrants, backing, qualifiers, and other aspects of a Toulmin argument. I’m not saying such specification isn’t useful, but it is a problem if it stops people from organizing and carrying out validity studies because they are overwhelmed by the complexity. However, it does not have to be that complex to engage productively in validation. At its core, validation is about making a logical case and collecting evidence to refute or support the things you say your test is designed to do.

Naturally, Lorrie Shepard said this more elegantly back in 1993. She proposed that validity studies be organized in response to the questions: “What does the testing practice claim to do? What are the arguments for and against the intended aims of the test? And, what does the test do in the system other than what it claims, for good or bad?” (Shepard, 1993, p. 429). I appreciate Shepard’s simplicity and focus on consequences, but less obvious is how following her advice would help evaluators prioritize the multitude of potential studies. Evaluators need to focus their investigations on those claims most crucial to the main use-cases of the test or testing program.

The recent exuberance about through-year testing provides a good case study. Several of us at the Center have been expressing concerns about such assessment approaches for a couple of years, including Brian Gong, Nathan Dadey, Will Lorié, and me. There is a line of research that could investigate the degree to which the results of tests administered throughout the year produce defensible summative annual determinations (a federal requirement) that are comparable to end-of-year tests. However, essentially all through-year programs claim that the results of the tests administered throughout the year can be used to improve instruction and learning opportunities for students. I did not ask these leaders to make such claims, but once they do, Shepard’s questions are even more relevant.

Lack of Guidance on Synthesis: The Aspect of Modern Validity Theory That Most Hinders the Practice of Validation

I think there are several things that hinder current validation efforts, such as users and developers pointing fingers at each other over who is responsible for what, and the current federal peer review process, which distracts users, at least at the state level, from carrying out meaningful validity evaluations. However, the question was about validity theory, so I focused my response on the lack of guidance from the AERA, APA, & NCME Standards (2014) or from most of our well-known validity theorists about how to put Humpty Dumpty back together. In other words, how should users weigh the various pieces of evidence to make overall judgments about the test or testing program?

Of course, Cronbach did not offer much comfort when he suggested a full employment act for validity evaluators:

Construct validation is therefore never complete. Construct validation is better seen as an ever-extending inquiry into the processes that produce a high- or low-test score and into the other effects of those processes (Cronbach, 1971, p. 452).

Ed Haertel, in his 1999 NCME Presidential Address, emphasized that individual pieces of evidence do not make an assessment system valid or not. The evidence and logic must be synthesized to evaluate the interpretative argument. Further, Katherine Ryan (2002) emphasized the role of multiple and diverse stakeholders in conducting validity studies. Therefore, the crucial activity of synthesizing validity arguments must meaningfully involve representation from diverse stakeholders so judgments about the validity interpretations and use are not the sole purview of the dominant group.

However, validity evaluations of most assessments or assessment programs include studies that are completed over a long timespan, either because of the nature of the studies or because users simply have to budget for a full evaluation over an extended time span. Thus, evaluators rarely have all the evidence in front of them to make conclusive judgments at a single point in time. Kane anticipated this issue by noting that evaluators can adopt a confirmationist stance when examining evidence generated early in a testing program, such as design specifications, item tryout data, and alignment reviews. But as programs mature, evaluators must engage in ongoing inquiry and interrogation as new evidence is produced, especially consequential evidence.

The reality of essentially all operational testing programs is that evaluators cannot simply advise the users to abandon or restart the existing testing program. Rather, if the evidence does not support the claims and intended inferences, test developers and users must quickly search for ways to improve the system. In rare cases, the evidence might be so overwhelmingly stacked against the intended claims that users are left only with the option of starting over.

The challenge in validating operational testing programs is not insurmountable, as Steve Ferrara and his colleagues at Cognia have illustrated. They have been using a validity argument to frame their technical documentation. They conclude with a summary of the available validity evidence collected to date and an evaluation of the degree to which the evidence supports the intended inferences and uses of the test and test scores (Cognia & MSAA Consortium, 2019).

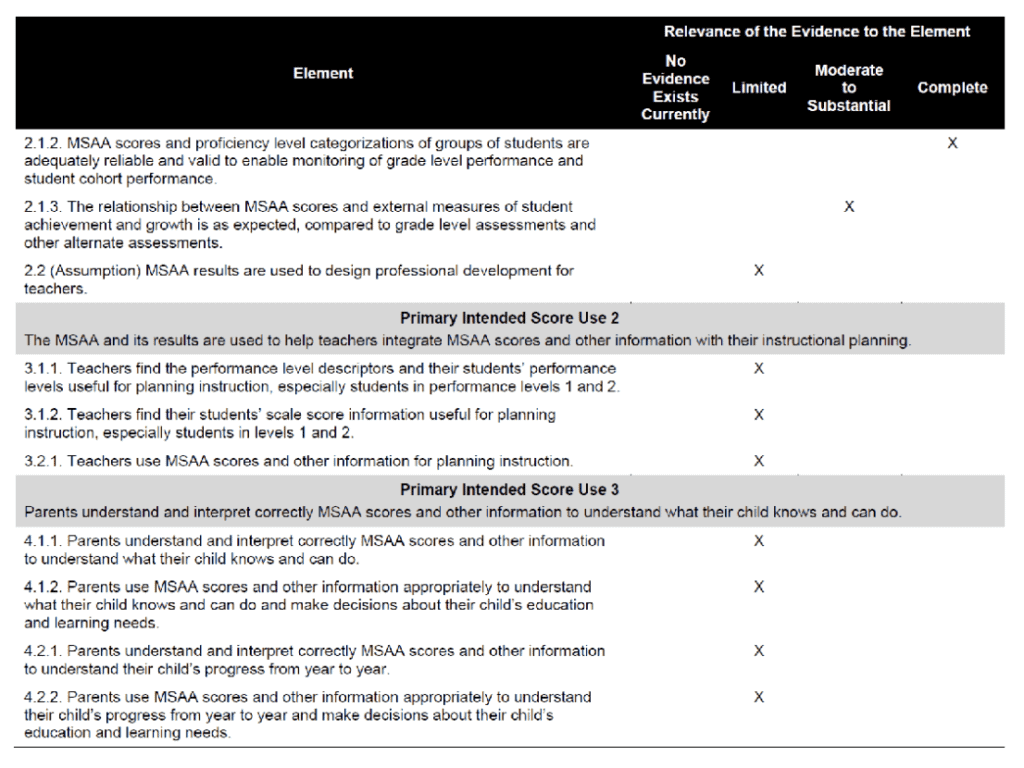

They summarize the evidence in what they call a “validity scorecard”, like the one shown below. The scorecard provides an easy-to-view summary that diverse stakeholders can review and deliberate on the quality of evidence and come to an overall evaluation of the testing program. I am not suggesting this is the only way to synthesize validity evidence and logic, but it serves as a useful example.

Closing comments

I appreciate being invited to be part of this session because, in spite of any differences, I think we all agree that there needs to be more of a focus on high-quality validity evaluations than we see in practice. I’m not just talking about state assessments. Interim assessments are so widely used for important purposes, such as purportedly improving instruction, that users deserve to have access to transparent validity evidence. Such evidence should not be hidden behind a proprietary wall.

Discussing both interim assessments and through-year assessments makes it obvious—in case it wasn’t obvious enough—that many assessments are being implemented to support some sort of action. Actions have consequences, which requires fully integrating evidence of test consequences into validity evaluations of these and essentially all testing programs.

Interim or through-year assessments are being implemented with stated goals of providing test-based information in order to help teachers gain insights into the learning needs of their students. Such implicit, and hopefully explicit, claims lead to questions that must be part of any validity evaluation.

Theories of action are useful for articulating the processes and mechanisms necessary for test scores to lead to improved instruction and, ultimately, to increases in student learning. For example, a theory of action might specify that teachers should be able to gain insights at a small enough grain size to target skills and knowledge that students had not yet grasped or identify what students need to learn next to maximize their progress. The theory of action is often a first step in validity evaluation. Laying out a theory of action helps identify the most high-leverage claims regarding test interpretation and use.

These through-year systems, as well as existing interim assessments, often come with strong assertions. But strong assertions require strong evidence. I have not yet seen the evidence, nor the logical arguments, needed to support many of the assertions associated with through-year designs. Those advocating through-year systems have a responsibility to produce evidence to support their major assumptions and to evaluate this evidence fairly. I am concerned about negative consequences as a result of mixing instructional and accountability uses in the same system. Therefore, there is an urgency to construct interpretative arguments and collect evidence, especially in terms of both positive and negative consequences.

I use through-year assessments as an obvious example of the importance of consequences as a critical feature of validity evaluations. Essentially all tests that those of us who attended the NCME conference deal with are designed to support uses that carry the potential for negative consequences. Therefore, as Suzanne and I argue in our forthcoming chapter, it’s time to put this debate about consequences to bed and recognize the centrality of consequences to validity evaluations.