A Culturally Responsive Classroom Assessment Framework

The Intersections of Equity, Pedagogy, and Sociocultural Assessment

Equity is a value undergirding public educational systems. Educational equity is about beliefs, and beliefs are lived out through actions and choices made relative to pedagogy, assessment, and education policy. Culturally responsive education (CRE) is a mental model or mindset that can be applied to help close equity gaps. There are many different frameworks for thinking about and applying CRE to design and evaluate culturally responsive classroom assessment. In this post, we build off Stembridge’s (2020) six themes of CRE to present a conceptual framework for the design and evaluation of classroom formative and summative assessments that follow from culturally responsive teaching and learning experiences.

Adapting a CRE Framework for Classroom Assessment

One of the challenges of adapting the CRE frameworks for the design or evaluation of classroom assessments is that most of the frameworks were not created with classroom assessment as the centerpiece. They are intentionally broad and inclusive, and therefore somewhat difficult to crosswalk between what CRE might look like instructionally and how those elements could be applied in terms of classroom formative or summative assessment.

We chose to work from Stembridge’s framework because we found it afforded the type of conversations we wanted to have with teachers in the context of designing and evaluating curriculum-embedded performance assessments. Teachers tended to see the immediate connections between Stembridge’s themes instructionally and the analog in terms of assessment. We believe these conversations would continue for all types of classroom assessments, not just performance assessments.

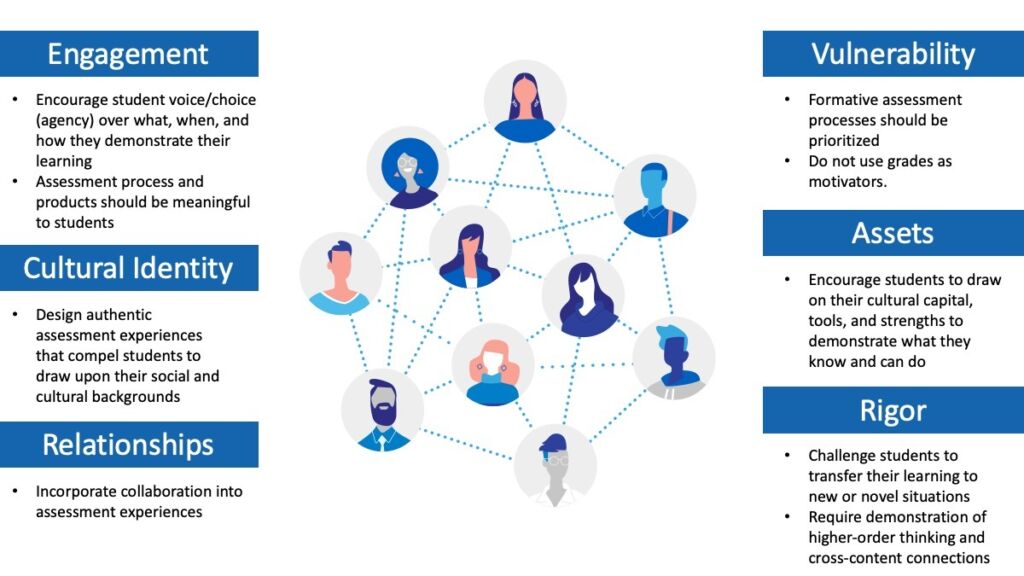

Figure 1 shows the Culturally Responsive Classroom Assessment Framework. The six themes of CRE from Stembridge include engagement, cultural identity, relationships, vulnerability, assets, and rigor. These six themes overlap but are listed separately to elucidate the connections with classroom assessment. In practice, they are impossible to separate. The bullets underneath each of the six themes of CRE in the figure are not intended to be an exhaustive list; however, it is difficult to imagine a summary of how the six themes relate to classroom assessment without these bullets being included.

Using the Culturally Responsive Classroom Assessment Framework in the Classroom

It may be helpful to examine classroom assessment systems to evaluate the extent to which they support culturally responsive assessment practices. Toward that end, we also developed a Culturally Responsive Classroom Assessment Inventory. This Inventory is intended to be used as a tool to help improve the cultural responsiveness of classroom assessments. The Inventory questions are embedded in each of the descriptions below.

These questions are intended to prompt reflection on the design of classroom assessments using Stembridge’s six themes of culturally responsive education. Not every question may apply to every assessment and some questions may seem repetitive because they re-state the same idea. For example, an assessment that engages students cognitively is rigorous and encourages student vulnerability and risk-taking.

Engagement

Engagement is both a theme and a goal for CRE. Engagement is a critical aspect of learning because attention drives learning. As Stembridge states: “Students’ engagement is the most valuable commodity in learning…if a student checks out during instructions, we can’t teach them anything” (p. 43).

One way to increase engagement is to allow students to have more ownership over what learning they demonstrate, and when and how they do so. This notion of student-led assessment supports assessment processes and products being more meaningful to students because they have agency over their learning.

An assessment could engage students behaviorally, such as through collaborative activities or hands-on investigations/data collection; affectively because of the emotional connection to the content or agency in the assessment design; or cognitively because of the rigor and intellectual challenge of the assessment.

- How does the assessment engage students?

Rigor

Rigor is about the mental processes taking place in the mind of the learner (e.g., fact recall vs. strategic thinking). Bloom’s taxonomy, Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge levels, and Karin Hess’s Cognitive Rigor Matrices are common ways of thinking about cognitive rigor.

Engagement and rigor go together. When a task is cognitively rigorous, students must be actively engaged in demonstrating, producing, and/or performing. And likewise, students are only authentically engaged, especially cognitively engaged, in the presence of rigor.

There must be multiple possible solutions or solution paths if students can construct their own interpretations.

- How does the assessment design encourage students to employ higher order thinking skills? In what ways are students led to construct their own meaning and interpretations from content when completing the assessment?

Cultural Identity

Two common models for thinking about cultural identity include Hammond’s (2014) Culture Tree and Edward T. Hall’s Cultural Iceberg Model (1976). Both models illustrate that culture is a matter of styles and surface appearances, and also that it creates much deeper ideologies that form the basis of core belief systems. The scope and depth of our cultural identities are not easily defined through the characteristics immediately observed by sight and sound.

Culture is also fluid and dynamic; and we are all multicultural beings in one way or another. During assessment design or evaluation, one can ask key questions about cultural identity. These questions are different ways of asking the same question.

- In what ways does the assessment make reference to culture?

- How does the assessment allow students to draw from their cultural knapsacks?

- How does the assessment support students in bridging their social/cultural identities with their academic identities?

Relationships

Relationships matter. Relationships are the channel through which a student’s investment in school is personalized. This concept relates to Geneva Gay’s (2018) notion of caring as one of the four critical aspects of culturally responsive teaching: “You can’t teach what or who you don’t know” (p. 1). Stembridge (2020) discusses the importance of relationships to CRE because “Relationships affirm for students that they have the right to school, that their school identity can co-exist with their other identities, and that meaningful relationships with individuals in school can extend to relationships with academic content, as well” (p. 88).

Relationships are integrated into assessment experiences through collaboration. Collaboration requires students to work interdependently to accomplish a group goal. A key question in assessment design or evaluation related to relationships includes:

- How does the assessment integrate collaboration into the assessment experience to enhance or deepen learning?

Vulnerability

One way to think about vulnerability is to think about the threats students face with respect to the context of learning and the learning environment. Students are vulnerable if their teachers have not prepared them to succeed on rigorous classroom assessments. Teachers must provide adequate formative assessment experiences, feedback, and modeling to support student risk-taking with respect to rigorous performance expectations.

Similarly, when relationships are considered a key aspect of cultural responsiveness such that collaboration is a valued aspect of some assessment experiences, it matters how students treat and talk to one another. Students need to be able to trust their peers and expect the learning environment to be supportive. In this way, vulnerability is related to rigor and relationships as it enables students to take risks with content, their teachers, and their peers.

- How does the assessment design (and the instruction that took place before assessment) encourage appropriate student risk-taking?

Assets

Student assets enable performance. Students use assets when they are faced with a challenging question, problem, or task. Habits of mind (Costa & Kallick, 2009) are performed, for example, in response to those questions and problems where the answers are not immediately known. Do students persist, manage impulsivity, think flexibly, and/or apply past knowledge to new situations? Similarly, do students draw on their cultural capital (Yosso, 2006) when faced with challenging assessment questions, problems, or tasks? Rigorous assessments require students to use their assets to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

- How are students able to draw on their assets to respond to the assessment?

Conclusion

Our framework builds on the culturally responsive assessment research literature by providing a conceptual framework for how CRE principles can be applied to design or used to evaluate the extent to which classroom assessments are culturally responsive (Lyons et al., 2021; Shepard et al., 2020). Future research can examine whether students find the classroom assessments developed using this framework are actually more culturally responsive in their individual experiences. Adapting ‘think aloud’ or cognitive lab procedures from large-scale testing applications may help collect this cultural validity and fairness information.

We acknowledge that one of the limitations of our framework is that some may argue it does not fully represent CRE because it does not position classroom assessment as a tool that can be used to disrupt structural systems of power and oppression (see, for example: Gay, 2018; Hammond, 2014; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Randall, 2021). In adapting an existing CRE framework for classroom assessment, however, we started with three key assumptions:

- Curriculum and instruction that serves the needs of all students should drive assessment design.

- No single teaching or assessment strategy alone will make anything or anyone culturally responsive—it’s about changing mindsets.

- We are uncertain the extent to which classroom assessment on its own can disrupt systems and structures of oppression.

For these reasons, the conceptual framework we presented in this post does not emphasize that aspect which is critical to some CRE frameworks. The role that classroom assessment can play as part of.an effort to disrupt systems and structures of oppression is an important consideration and one that should be examined in the future.