Technical Advisory Committees: A Counselor for Your Assessment Program

Guidelines for Getting the Most out of Interactions with Your Technical Advisory Committee

What kind of advisor is right for you? Advisors come in all different shapes and sizes and may not even have the word advisor in their name. We likely all have some experience with an advisor of some form or fashion: a high-school counselor, legal counsel, financial counselor, or certified counselor. A well-formed Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) can serve as a combination of all of these types of counselors for your state or district assessment program.

Most of us will have had at least one sit-down conversation with the high school counselor helping us think through possible futures. We may have interacted with legal counsel, whether at work or under some other less than desirable circumstance. A financial counselor is also a popular one, as we can all be better money managers. Perhaps closer to our professional lives, there are also executive counselors who focus on self-awareness, goal-setting, action-planning, and monitoring results. Then there are certified counselors (sometimes referred to as therapists). They tend to provide structure to approaching problems and typically require a degree and certification to work with clients.

Counselors rely on evidence-based strategies to help you engage in your own needs assessments, self-examinations of your own capacity and shortcomings, establishing actionable plans for improvement, and building better habits through self-awareness, self-care, and perhaps even reducing your own toxic self-criticism. States and districts would do well to also adopt a similar continuous improvement approach to their assessment programs.

The Application of Counseling to Large-Scale Educational Assessment and Accountability

One can apply the idea of counseling and seeking advice to large-scale educational assessment and accountability through Technical Advisory Committees (TACs). A good TAC is like a good counselor for your assessment program. While some would argue a counselor is not necessary, I disagree. Given the task of managing an assessment program, we could all benefit from someone to talk to, think through issues with expertise and honesty, and help establish a continuous improvement process. After all, it is a critical type of self-care that one should not overlook.

Much like finding the right counselor and leveraging their advice, forming a TAC and using their insight requires some preparation, advanced planning, and continued effort after you meet with them. Below, I offer four considerations that I expand upon in my recent policy brief that can help you form and use a TAC well and may even provide some insight into getting the most out your own self-care-focused continuous improvement process.

1. Find the advice that makes the most sense for you.

Getting the right advice means finding the right people. To find the right people you need to know the scope of your problem. By first determining the scope of advice you need, be it ESSA accountability assessments, alternate assessments, English language proficiency assessments, or whole-sale assessment systems (see Marion, et. al., 2019), you can then start identifying the categories of expertise you need in your TAC. Also, accountability systems have their own unique technical requirements, challenges, and concerns where states and districts may benefit from technical advice (D’Brot, LeFloch, English, & Jacques, 2020).

2. Determine the structure that gives you the advice you need.

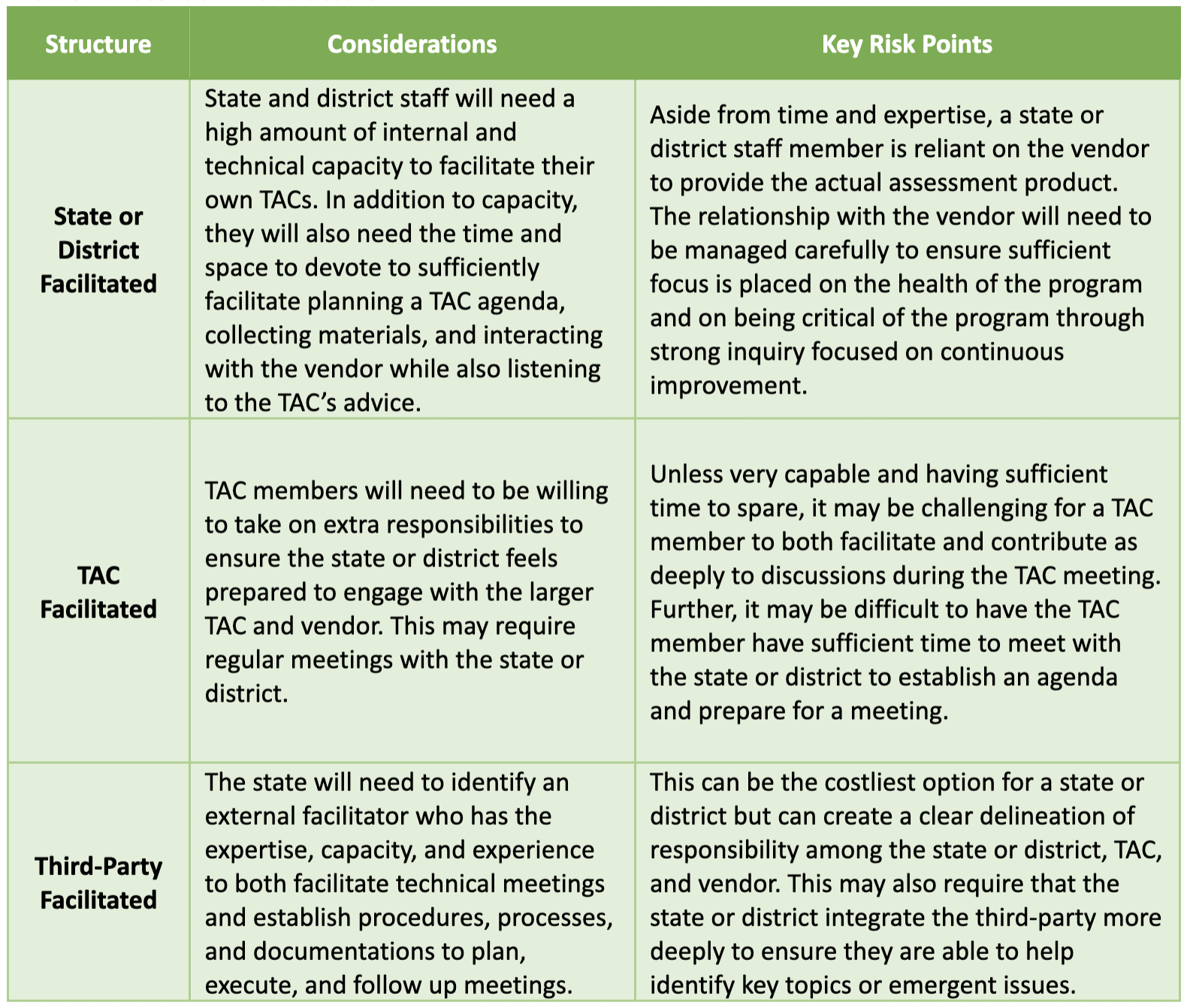

As with counseling, you must determine how you want your sessions to operate and how much you will share with others. How do you want your TAC to be positioned? Will you establish TAC meetings as open or private? Because of local policies, rules, and regulations, this decision can rarely be made alone and will likely require guidance from your legal counsel (see what I did there?). Additionally, you will also want to define the processes that govern a TAC, which could range from a formalized voting and approval process to an informal structure where the TAC advises. Finally, you need to consider how a TAC is facilitated, which is separate from how a TAC is logistically managed. I offer three potential structures that a state or district may employ to their TAC in the table below.

Please note that I did not include a vendor-facilitated TAC as an option. While I have seen this approach used in the past, it is far less effective and could result in problems, both optically and operationally. The TAC best serves state leaders when it provides direct and honest advice that, at times, may be critical of the test vendor. Having a vendor-run TAC creates a conflict of interest and generally lacks an understanding of policy requirements, practical constraints, issues that exist outside of the program (of which there are many), and solutions that may not be the most efficient or cost-effective.

3. Plan, plan again, and follow through with the advice you receive.

Like a personal counseling session, you need to have a solid approach to your meetings.

- Planning the agenda for a TAC meeting means being prepared with the appropriate documentation, materials, or presentations well in advance of the meeting and being sufficiently prepared to address the questions that will come up throughout the meeting.

- Preparing and sharing materials is closely linked to planning the agenda. TAC meeting preparation should begin at least two months in advance, which will ideally enable the state or district to develop and connect materials to the agenda and ensure that all other parties (e.g., vendors, state/district partners, stakeholder representatives) are prepared and able to participate accordingly.

- Facilitating the meeting relies heavily on the previous activities. Throughout the TAC meeting, the facilitator should be actively taking notes, soliciting feedback from TAC members who may more reticent, and identifying action items for the relevant attendees.

- Following the meeting, the facilitator should compile the meeting minutes into a workable summary that can be shared with the TAC and other meeting attendees.

In addition to the above points, we need to be thoughtful about the schedule and structure of our meetings, including how often to convene in-person and virtual meetings.

4. Understand how the advice given to you fits into your larger context.

The assessment ecosystem is a large one that begins with standards development and continues well into use and interpretation. It is important to keep the TAC focused on the recommendations they are best equipped to address. Your TAC won’t know what you don’t tell them, which requires that you determine which local issues, climate, and context background the TAC must be aware of to provide the support you need. A strong TAC can a powerful ally to your program(s), however they are not your only feedback group. Consider how TAC recommendations could and should be balanced against other stakeholder groups to inform programs most appropriately.

Concluding Thoughts

Selecting, managing, and facilitating TACs can be a potentially intimidating endeavor, but well worth the challenge if handled thoughtfully (the same could be said for personal counseling). The problems that TACs can best support are often technical but must also be couched in the reality of policy, practical, and political constraints. Integrating any advice you might receive from your own TAC, along with the recommendations of other stakeholder groups, can position states or districts well when tackling complex problems.

I invite readers to review the more detailed brief, which provides a series of concrete recommendations and considerations when thinking about forming a TAC, managing meetings, and leveraging advice.